One of the most perplexing moments in Soviet history was the decision to have Lenin’s body immortalized in a public mausoleum for all to see. In retrospect, one cannot help but view this as deeply antithetical to the radically materialist and atheist political culture of the Bolsheviks, whose scientific outlook was bound up with a sharp critique of superstitions and religious practices. The transformation of Lenin as a sacred idol entombed within a majestic temple-like structure cannot help but recall the Orthodox saints of Russia’s past or Egyptian Pharaohs of another era. Indeed, this criticism was not lost on many Bolsheviks. Trotsky and Bukharin sharply critiqued the preservation of Lenin’s corpse as a form of religious relic worship, and Lenin’s widow Krupskaya privately objected and never visited the mausoleum.1

Yet, the Bolsheviks who spearheaded this morbid initiative vehemently rejected any connections between Lenin’s preservation and traditional religious practice; Enukidze had defensively noted that “it is obvious that neither we nor our comrades wanted to make out of the remains of Vladimir Ilich any kind of ‘relic,’” insisting that the embalming was intended to preserve Lenin’s features in perpetuity so future generations could witness the great Soviet hero.2 A closer look at the history of Lenin’s “immortalization” reveals that this process was shaped by ideological currents in utopian Bolshevik thinking, particularly Russian Cosmism and God-Building. In this way, Lenin’s preservation marked a significant departure from other historical instances of mummification, as it was never treated by the leadership as being connected to an afterlife, but was instead related to techno-futurist themes of scientific mastery over nature and biological renewal.3 At the same time, the emerging Lenin cult absorbed symbolic and emotional functions typically associated with spiritual devotion, and the mausoleum became a natural expression for this. In the following pages we will see how these ambiguities, interrelations, and complexities shaped the context of Lenin’s preservation.

The Lenin Cult

While the slavish Lenin cult is typically associated with the Stalin era, its origins can be traced to the final year of Lenin’s life, during his illness, when it began to take shape through the collective efforts of leading Bolsheviks. The anthropologist Alexei Yurchak distinguish this highly curated, idealized post-Lenin Leninism from Lenin’s own views and ideology. Yurchak writes:

While the politburo was isolating the living Lenin from the political world, it was simultaneously engaged in canonizing Lenin’s public image. ‘‘It was at that time, [from 1922 and] until Lenin’s death in January 1924, that most mythological images and institutions that were formed around Lenin’s cult were created. A precondition for this was the loss by Lenin at that time of his unmatched personal aura.’’ More than a year prior to Lenin’s death, and in spite of his active protestations, the party leadership introduced the term ‘‘Leninism’’ into public circulation.4

This is why I will use Leninism to refer not to Lenin’s own worldview, but to the meticulously crafted political memory of Lenin and his thought. This was not a wholesale fabrication; there were certain continuities and overlaps between the posthumous Lenin and the living one. However, Leninism assumed a flexible form, its emphasis shifting depending on how it could be politically instrumentalized by those seeking to brandish their communist credentials and affirm their fidelity to what was presented as the one true Leninism. Just as American political actors continually reinterpret the Constitution to legitimize competing visions of governance, Soviet leaders treated Lenin as a foundational text; his personhood was dissolved into the Party’s abstract, total authority and Leninism then became inseparable from the foundational central institutions that constituted the Soviet state.

Lenin was the central originary symbolic object of Soviet communism. Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and Gorbachev each represented their governance as a break from that of their predecessor, and each, in different ways, appealed to a return to Lenin, presenting themselves as orthodox interpreters of the USSR’s foundational figure.5 Lenin’s status as the greatest Bolshevik was an ironclad consensus formed in the early history of the Soviet Union. Trotsky had written that “Marx was a prophet with Mosaic tablets and Lenin is the greatest executor of the testaments.”6 Similarly, Zinoviev referred to Lenin as “a god-sent leader, one of those who is born to mankind once in a thousand years.”7 The Old Bolshevik Bonch-Bruevich praised Lenin as a “prophet of the proletariat.”8 The decision to preserve Lenin for eternity can only be understood within this context of quasi-religious devotion in which, surprisingly, uncompromising Bolshevik atheists drew on the imagery and rhetoric of the Christian Bible to express the extent of their adoration of Lenin. Even before Lenin had passed, the sacralization of Lenin had already begun:

From early 1923, the leading party propagandists started insisting on the necessity to pledge party allegiance to ‘Leninism.’’’ On March 31, 1923, nine months prior to Lenin’s death, the party established the ‘‘Lenin Institute’’ in Moscow. In the summer of 1923, Pravda appealed to its readers: ‘‘‘Every scrap of paper’ bearing an inscription or mark made by Lenin could provide an important contribution to an understanding of the great man.’’ Later the newspaper added: ‘‘‘Any bit of paper typed on a typewriter,’ if it carried the signature of V. I. Lenin, should be sent in to the Institute.’9

This process of sacralization was complicated by the ordinariness of his physical death, which, to the Soviets, did not adequately reflect the magnitude of his historical greatness. In a 2021 medical analysis, Norbert Nighoghossian, Head of the Neurology Service of the Vascular Neurology Department of the University Hospital of Lyon, concluded that Lenin’s death was “consistent with a severe atherosclerosis,” and that it could “be explained by an inherited lipid disorder.”10 Nighoghossian also writes that “stress may also have played a role in the progression of his atherosclerosis,” while acknowledging that his conclusions are not definitive given that many relevant medical documents remain classified.11 The Soviets themselves were not interested in publicizing the actual details of Lenin’s death:

Pravda published two long articles (November 1990) by surgeon Boris Petrovskii (Petrovskii 1990a, 1990b), a member of the Soviet Academy of Medical Sciences and former minister of public health. Petrovskii wrote: “Lenin certainly did not have the so-called inherited arteriosclerosis—an illness of much younger age.”12

They argued the cause of his fatal stroke “[was] purely external,” a result of “superhuman mental activity” and “enormously hard labor.”13 Lenin’s bullet wounds from a previous assassination attempt were described as a secondary cause. Yurchak notes how Lenin’s arteriosclerotic degeneration and dysfunction were referred to as “wounds” due to their supposedly “external” nature. In this way, Lenin’s death could be constructed as an act of martyrdom; the Bolshevik hero was killed by the immense burdens he bore in service of the revolution and socialist construction.

Lenin left big shoes to fill with his passing, and his absence loomed large. Competing Bolshevik elites, including Stalin, Trotsky, Bukharin, and Zinoviev, vied for ideological authority by claiming fidelity to Lenin’s legacy. Despite disputes over the meaning of Leninism, Lenin’s authority itself was never questioned in any meaningful sense. The construction of a Lenin cult was not only politically expedient for Lenin’s potential successors, but also held together the USSR’s fragile political structure in the wake of revolution and civil war; the cult of Lenin functioned as a unifying symbolic mechanism. Tumarkin notes how the tense factional battles of the succession crisis also posed a risk of another civil war—a possibility none of the Bolshevik leaders wanted.14 In crafting the cult of Lenin, his successors simultaneously defined the boundaries of political legitimacy and positioned themselves within them.

Although the most significant contributor to the shaping of the Lenin cult—as it endures to this day—was unambiguously Stalin, it was his Foundations of Leninism that arguably became the single most influential text in forming the broad popular understanding of Lenin, inaccuracies and all. This is the argument of Lars T. Lih, a preeminent scholar of Lenin. Lih Writes:

Stalin’s Foundations of Leninism, written immediately after Lenin’s death, is by far the most influential contribution to Lenin studies ever made. Its impact has nothing to do with one’s political attitude. Indeed, the writers who are the most staunchly anti-Stalinist (the Trotsky tradition and the academic historians) are often the ones most loyal to the distortions introduced by the Soviet leader.15

Stalin’s text, while broadly accurate in summarizing Lenin’s political views, fashions a mythic image of him as a lone genius who single-handedly shaped Marxist theory. Central to Lih’s argument is that Foundations of Leninism effectively “airbrushed” the revolutionary left wing of the Second International from history—a wing that included Lenin—and portrays him as entirely opposed to the organization in its entirety.16 Stalin also portrays Karl Kautsky, once revered by Lenin as a leading Marxist thinker before their break over World War I, as Lenin’s ideological foil and the embodiment of the failures of the Second International. As the main forum for socialist theory and strategy worldwide, the Second International was the site of major ideological debates in which Lenin was an active participant. Stalin was not interested in highlighting these internal contradictions within the socialist movement, and instead presents Lenin as being wholly opposed to the Second International itself and its transgressions of “philistinism, narrow-mindedness, political scheming, renegacy, social-chauvinism and social-pacifism.”17 This text played a key role in distinguishing the historical Lenin from the idealized figure that came to dominate popular consciousness, as the former became subsumed by the latter.

Without the problematic intellectual heritage of Kautsky, Lenin can become a theoretically original political genius and assume his proper place as the Great Teacher of the Soviet Union. This was at odds with how Lenin viewed himself, which was as “a great political leader, not a great political theorist.”18 Lih describes how this politicized memory shaped both the internal dynamics of the Communist Party and the broader contours of Marxist discourse for decades. It defined how Lenin and the revolution would be understood and invoked throughout Soviet history.

Long after this text, Stalin continued to cultivate and refine this belief of Lenin as the foremost communist authority, far above even himself. In David Brandenberger's Stalin’s Master Narrative, he reconstructs Stalin’s writing process in making the Short Course on Party History, the official, state-sanctioned “master narrative” that defined Soviet ideology.19 Access to Stalin’s editing process is highly revealing of how Stalin viewed his own place in the Soviet system. Brandenberger describes how the ruler had “cut dozens of paragraphs and scores of parenthetical references relating to himself and his career.” Stalin sought to temper his personality cult and, at times, seemed embarrassed about it. These cuts to fawning segments about himself were done in part to avoid eclipsing what he viewed as more important themes, such as the paramount significance of Lenin and Leninism:

Perhaps most dramatic within this editorial process was Stalin’s elimination of all commentary on his own prerevolutionary career in the Transcaucasian underground and virtually all its detail on local Social-Democratic organizations, both in Transcaucasia and elsewhere. Such cuts, which even deleted the names of prominent Old Bolsheviks, continued through Chapter Five and had the effect of concentrating historical agency around Lenin and the Bolshevik movement’s central institutions.20

While cults of personality have been common throughout history in a variety of political settings, it must be noted that the cult of Lenin took on a unique form specific to its Soviet context. Ken Jowitt, writing on this topic, is instructive. Jowitt describes how, historically, traditional regimes located their sovereign power in the personhood of an individual who led a social order based on ascribed status and established customs; this is in contrast to modern states, which typically locate their sovereign power in the nation’s impersonal bureaucratic systems and institutions of governance.21 The Soviet system, Jowitt argues, seemed to combine elements of both, synthesizing “the fundamentally conflicting notions of personal heroism and organizational impersonalism and recast them in the form of an organizational hero, the Party.”22 This model, Jowitt continues, “expresses itself in the conception of the Party as an amalgam of bureaucratic discipline and charismatic correctness; and as a heroic principle whose combat mission is more social than spiritual or military.”23 Indeed, the Soviets had a highly voluntaristic conception of the Party form, which was to function as an active agent of history, moving society along its epic historical mission toward the societal endpoint of “full communism”—and actively intervening as necessary.

The Party, an essentially bureaucratic and institutional form, was imbued with charismatic and heroic traits, embodying the valour reminiscent of protagonists in socialist realism novels or Stakhanovite shock troops on the factory floor.24 What Jowitt does not grasp, however, is that the Communist Party was not just a synthesis of existing political systems, but, as scholars like Khalid Adeeb and David Priestland argue, was a mobilizational one—a state that drew its legitimacy from its ability to generate active participation and popular enthusiasm among its citizens.25 This does not mean electoral democracy or institutional participation, but rather generating mass buy-in for various state-led initiatives, such as mass literacy programs, the productivity cult (Stakhanovism), or anti-religious campaigns, for instance. This mobilizational impulse was part of the Soviet state’s Marxist lineage as a self-described workers’ state engendered by a mass workers’ movement. Lars Lih describes the emotional core of Bolshevism as “heroic class leadership,” writing that Bolshevism was “not a doctrine constructed out of abstract propositions, but as a narrative with a central theme of inspiring class leadership. The Party inspires the Russian workers who inspire the Russian peasants to create together a worker-peasant vlast that will inspire the world by building socialism.”26

Although the politics of heroic class leadership ran into certain problems. In the wake of the Revolution, Marxist theory was not easily accessible to a largely uneducated and illiterate population. The abstract ideological framework of Marxism could struggle to generate immediate, organic popular enthusiasm in many segments of society.27 This is in contrast to simplified hero narrative rooted in long-standing Russian folkloric traditions, which were instantly recognizable and emotionally resonant for much of the population. For the leadership, these narratives served to bridge Marxist-Leninist theory and the lived experience of Soviet citizens. Lenin’s rendering as a Great Hero served an important role in legitimizing the Soviet state for its citizenry in a way that was also ideologically acceptable for the leadership.

Getty writes that much of the Lenin cult “came from below.”28 The decision to have Lenin preserved for eternity was no doubt influenced by the intensity of popular despair in the wake of the Bolshevik leader’s passing. Everyday citizens took part in the commemoration of Lenin and did so in ways that sometimes unsettled the leadership or exceeded what they viewed as the acceptable parameters of mourning. People across the provinces independently proposed ways to honour Lenin, like naming places after him or constructing monuments. The Dzerzhinskii Commission, tasked with overseeing Lenin’s commemoration, spent much of its time rejecting proposals from citizens, including over-the-top requests, such as an electrified mausoleum with lightning bolts, as well as renaming calendar months, since, as one supporter put it, “Lenin was savior of the world more than Jesus.”29 Though the Soviet state soon moved to centralize and regulate these expressions, it was clear that the Lenin cult had tapped into a deep cultural reservoir. Getty writes:

Though, from the very beginning a popular impulse and input stimulated, if not caused and created, the official actions. Thousands of unsolicited condolence letters and telegrams spontaneously poured in. The very decision to move Lenin’s body from the Hall of Columns to Red Square had to do with crowd control and was the result of thousands of requests from the public, especially from those unable to reach Moscow in time to see the body during the viewing period originally planned. The decision to build the second, “temporary” wooden and then the third permanent stone mausoleum had similar causes: the people kept coming, more than a hundred thousand in the first six weeks, despite bitter cold.30

Indeed, many everyday citizens genuinely seemed to have conceived of Lenin as a Christ-like Biblical figure. One letter from a peasant described Lenin as: “the great genius of mankind, such as is hardly born once in a thousand years. His whole life he suffered all kinds of deprivations … he won freedom for the poorest people, emancipating them from the power of capitalism.”31 From the moment of his death, popular responses surged with a religious intensity. Mourners flooded Moscow with telegrams and letters, pleading for access to the body or proposing commemorative acts. This outpouring was closely studied by Soviet agitators, and ideology workers who based their agitational efforts on “all written materials demonstrating soldiers’ and peasants’ reactions to Lenin’s death.”32 Typically, official Soviet state ideology is assumed to be an artificial, top-down imposition, but, as in this case, it often involved a more nuanced interplay between “top-down” and “bottom-up” dynamics. Tumarkin notes that these devotional depictions of Lenin during the early years of the Soviet state “were probably not responses to institutional directives. No apparatus existed at this time to indicate the appropriate epithets and images.”33

Given that the USSR in part based its legitimacy on its ability to mobilize its masses in service of state objectives, this upswell of public interest in Lenin’s body must be considered a major factor in the body’s “immortalization.” In the absence (and rejection) of traditional nationalist, religious, or monarchical symbols, Lenin’s embalmed body became a foundational icon for a Marxist state, a revolutionary relic that anchored collective identity and offered a physical site around which political mythology and state legitimacy could cohere.

The Body

Though the actual deliberative process behind the decisions of Party leaders to embalm Lenin’s body remains murky, scholars have nevertheless been able to glean some insights. Tumarkin recounts the initial debate over how Lenin’s funeral and potential preservation transpired, describing how Stalin initially suggested that Lenin’s body be embalmed and preserved, not forever, but at least “long enough time to permit our consciousness to get used to the idea that Lenin is no longer among us.”34 Rykov and Kalinin took Stalin’s side, while Trotsky and Bukharin seemed horrified at the notion of reducing Lenin to a relic. At this point, no one had discussed the possibility of preserving Lenin for eternity without decay; indeed, they likely did not believe the technology for such an endeavour even existed.35

Soon after Lenin’s death, it was decided that the body would be buried forty days later, and embalmed for this duration. At some undetermined point, forty days became eternity.36 It is likely that this decision was not made all at once but emerged pragmatically and contingently, as Party leaders gradually came to recognize its political utility and scientific feasibility; Yurchak notes that once they started down the path of experimental bodily preservation, “there was no coming back.”37 Tumarkin observes that, according to Konstantin Melnikov, the notion of “permanently preserving and displaying Lenin’s body” originated with Leonid Krasin.38 Krasin, an engineer and social entrepreneur, was particularly fascinated with preservation and spearheaded the first failed attempt to preserve Lenin through cryogenics. Indeed, the initial attempt to preserve Lenin’s corpse was fraught with difficulties. Tumarkin recounts a wide range of debate among Party leaders and officials on the topic of Lenin’s preservation:

Central Committee member Vyacheslav Molotov opposed both freezing the body and submerging it in liquid but had no alternative suggestions. Doctor Maksimilian Savel’ev proposed putting the body in a transparent capsule filled with pure nitrogen—neutral gas that would prevent biological pro- cesses and stop decomposition, he argued. But Krasin was skeptical: ‘‘I have my doubts.. . . As far as I know, apart from the bacteria that live in oxygen there are also anaerobic bacteria that successfully function in nitrogen.’’ Having listened to these opinions, Avel Enukidze, member of the Central Executive Committee, summarized: ‘‘We should certainly understand that we will not be able to preserve Vladimir Ilyich for a long time.. . . We will freeze the body without promising to anyone that this is done for posterity. If disaster strikes and it continues changing even when it’s frozen, we will have to enclose it.’’ Then Kliment Voroshilov, member of the Revolutionary Military Council, made the final suggestion: ‘‘I propose doing nothing. If the body holds up for another year without change, this is already good enough.39

They eventually proceeded with a cooling system: a duplicate refrigeration unit was used to maintain adequate temperatures.40 This ensured a backup in case the main system failed. However, to the dismay of the leadership, Lenin’s body soon showed signs of decay as rising temperatures caused visible skin discolouration. The Funeral Commission then invited a team of scientists to explore methods of halting the deterioration and maintaining the body in a viewable state. They sought to preserve Lenin’s external appearance, especially his facial features, as closely as possible to how he looked shortly after death. The embalming effort was demonstrative of fairly significant advances in the science of bodily preservation.41 Led by biochemist Boris Zbarsky and anatomist Vladimir Vorobiev, the team of scientists employed a method of dynamic preservation, involving regular chemical treatments and structural reinforcement of tissues. Even to this day, Lenin’s preservation is an ongoing and painstaking process of bodily renewal, requiring continual refinement—his lifelike skin tone and facial features are maintained through meticulous injections of artificial compounds. The team’s efforts also involve more than just Lenin’s body; the biochemists facilitate ongoing experiments on other cadavers to further help refine the process of Lenin’s preservation.42

It is worth noting how the experimental nature of Lenin’s preservation has led to scientific discoveries that have actively helped living patients. Yurchak writes that the process has enabled “a greater understanding of the nature of human tissues, creation of artificial replacements, and even inventions in other areas of medicine.”43 A life-saving technique of kidney transplantation pioneered in the USSR by Lopukhin during the 1960s was influenced by research conducted on Lenin’s body.44 The process also led to the development of a noninvasive “three-drop test” for measuring skin cholesterol, an approach later patented in the U.S. and now commonly used in American medicine.45

Science and Spirituality

Commitment to scientific progress has been a part of Lenin’s preservation from the very beginning. Early on, the Soviets publicly admitted that the first attempt at preservation was imperfect and that Lenin’s body had begun to decay, but that subsequent re-embalming efforts were proving successful thanks to Soviet scientific expertise. Tumarkin writes:

The commission’s willingness to share with the public the initial decomposition of Lenin’s body is remarkable and demonstrates that its members were in no way attempting to pass off the preservation of the corpse as miraculous. On the contrary, they were celebrating the expertise of Soviet science.46

The Soviets outwardly rejected traditional religious superstitions that claimed holy figures could resist bodily decay as proof of their sanctity. They had no illusions about the inevitability of decomposition. Indeed, “early Soviet atheist activists … worked to discredit religious belief by tearing open the saints’ caskets to demonstrate that the relics either possessed no special powers.”47 Still, Soviet leaders believed that nature’s laws could be overcome—not by God’s divine intervention, but through scientific innovation and the indomitable socialist work ethic under the heroic class inspiration of Soviet leadership. This carried a millenarian and utopian impulse that gave rise to a vision of the historical mission of communism as not only transforming society, but transcending the limits of the human body.48

This unwavering faith in human ingenuity and socialist progress replaced the notion of divine miracles, as supernatural wonders gave way to the belief in labour miracles, herculean wonders carried out by those inspired by the Soviet cause.49 This mindset was not unique to Lenin’s preservation; it reflected a broader popular belief in the Stalin era, in which visions of utopia were built on top of deep-rooted cultural foundations, a striking fusion of techno-futurism and vaguely familiar age-old folklore, resulting in an entirely new mythos that felt both hyper-modern and superstitious. Rosenthal writes:

The rhetoric of miracle permeated all spheres of Soviet discourse of the Stalinist era. Popular songs, those mass-culture repositories of guiding myths, asserted that "we are born to make fairy tale into reality, / to conquer time and space […]" and that "simple Soviet people create miracles everywhere […]."The mass media informed Soviet citizens daily about the "miracles of heroism […]" being performed by Stakhanovites and other shock workers at factories and collective farms, and about model soldiers guarding "the sacred Soviet borders […]." In the opening speech at the First Congress of Soviet Writers, Maxim Gorky urged fellow writers to depict the miracles taking place "in the land illuminated by Lenin's genius, in the land where Joseph Stalin's iron will works tirelessly and miraculously.”50

The Soviet push toward modernity could not fully sever itself from the historical past, and its utopian aspirations were shaped, in part, by enduring folkloric, religious and mystical traditions. One cannot discount the residual influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity, as even Stalin had initially called for Lenin to be buried in the “Russian manner.”51 Though this influence is sometimes overstated. Tumarkin describes how Lenin’s funeral was quite unlike any Orthodox ceremony:

In a traditional Orthodox funeral, prayers are said, of course, and at the very end of the ceremony the priest sprinkles the coffin with earth, ashes, and oil. A requiem is chanted as the body is lowered into its final resting place. At the final moment of Lenin’s funeral, absolutely nothing was said. No earth was sprinkled on his coffin. No last rites of any kind were performed on the body of the deceased leader. 52

Yet, the eternal preservation of a body cannot be separated from the implicit mystical or spiritual connotations such an act implicitly carries. More influential than Orthodox Christianity, was the influence of Bolshevik mystical thought. The ideological currents of Russian Cosmism and God-Building produced unique forms of Bolshevik spirituality that were intended to fulfill the void of religion but within the parameters of Bolshevik revolutionary-utopianism. Cosmism is closely related to the figure of Nikolai Fedorov, an Orthodox Christian philosopher who is widely regarded as the philosophy’s founder. His philosophy centred on humanity’s collective duty to overcome death through scientific progress, which went on to become a major influence on later utopian thinkers and movements in Russia and the USSR.53 His vision of the “common task” anticipated resurrection of all people who had ever lived on Earth. Early Soviet utopian thinkers reworked these kinds of millenarian themes within their materialist, revolutionary paradigm.

Indeed, Bolshevik philosophers often did not discriminate in their ideological influences. Nikolai Anatoly Lunacharsky, the future Soviet People’s Commissar for Enlightenment, was in a shared exile with Christian existentialist Nikolai Berdyaev. Here, there was a degree of ideological cross-pollination. Berdyaev had informed Lunacharsky of the irrepressible spiritual core latent in Marxism despite its self-conception as a strictly materialist ideology:

The passionate desire of the “orthodox” [Marxists], my opponents, to defend the totality and purity of their ideal was always dear to me, since I see in that [desire] the ineradicable idealism of the human spirit which bursts through material limitations. But this idealistic demand … can find its true satisfaction only in a new “faith” in the creation of which we must now work.54

This call for a new faith clearly left its mark on Lunacharsky. The Bolshevik God-Building movement, which Lunacharsky led, sought to replace traditional religion with a secular faith in humanity as God.55 Recognizing religion’s psychological power, Lunacharsky redefined divinity as the symbolic expression of humanity's highest collective ideals. He professed that “it is necessary for humanity to almost organically merge into an integral unity. Not a mechanical or chemical … but a psychic, consciously emotional linking-together … is in fact a religious emotion.”56 This new faith sought not only to inspire solidarity around these unifying spiritual themes, but elevate humanity itself, which was to become “a single interconnected, sapient organism, immortal and infinite like God,” a process of evolutionary transformation in which the proletariat was to lead.57 In 1906, Lunacharsky boldly declared that “God will be man himself.”58 However, by the time the early Soviet state established itself, God-Building was already going out of fashion. Harshly condemned by Lenin as being irreconcilable with scientific socialism, there was now no place for a potential state-sponsored Soviet religion, as the leadership consolidated an ideology of strict state-atheism. While Lunacharsky’s subversive theological declarations would no longer be acceptable by the 1920s, deification became possible by other means. The main proponents of God-Building continued to play a major role in Soviet governance and still retained strong mystical-humanist leanings, even if they no longer explicitly associated with these movements.

For instance, Anatoly Lunacharsky was put in charge of the cultural and ideological planning for Lenin’s Mausoleum. Leonid Krasin likely played the most prominent role in Lenin’s preservation efforts, and was also a central figure in the Bolshevik God-Building movement.59 Krasin’s worldview was influenced by the Bolshevik Alexander Bogdanov, whose own experiments with biological rejuvenation ultimately cost him his life—he died after receiving a blood transfusion from a student infected with malaria as part of an experiment to extend his lifespan.60 Following Fedorov, the Bolshevik God-Builders had a fascination with interrelated themes of scientific pursuit, immortality, and resurrection. Krasin, at a comrade’s funeral, had pronounced that a day would come when the Soviets would be able to resurrect the dead:

And I am certain that when that time will come, when the liberation of mankind, using all the might of science and technology, the strength and capacity of which we cannot now imagine, will be able to resurrect great historical figures61

While those associated with the God-Building movement had distanced themselves from the grand religious ambitions from years prior, it’s hard not to see how these mystical urges were in some sense redirected into Lenin’s immortalization. Tumarkin writes that “God-building—and the later immortalization of Lenin—sought a true deification of man.”62 These advocates of Bolshevik spirituality found an opportunity in Lenin’s death, a flesh and blood corpse they could build their God out of. It is a bitter irony of history that Lenin, the fiercest critic of God-Building—at one point condemning such efforts as necrophilic—would himself become its "man-god," as Tumarkin put it.63 However, Tumarkin may be at risk of overstating her argument of Lenin becoming a kind of god. The political sacralization of Lenin was distinct from explicitly religious processes of deification, in which historical people were later characterized as possessing divinely appointed supernatural abilities or being demigods in a literal sense. Lunacharsky’s original vision of God-Building did not include veneration of any single individual, instead emphasizing the collective humanity of transformation into godhood, but the banner of Leninism, nevertheless, came to express a similar ideal through the body of Lenin himself; not as a divine individual, but as a moral centre and enduring symbol of the proletariat’s collective struggle through the leadership of the Party.

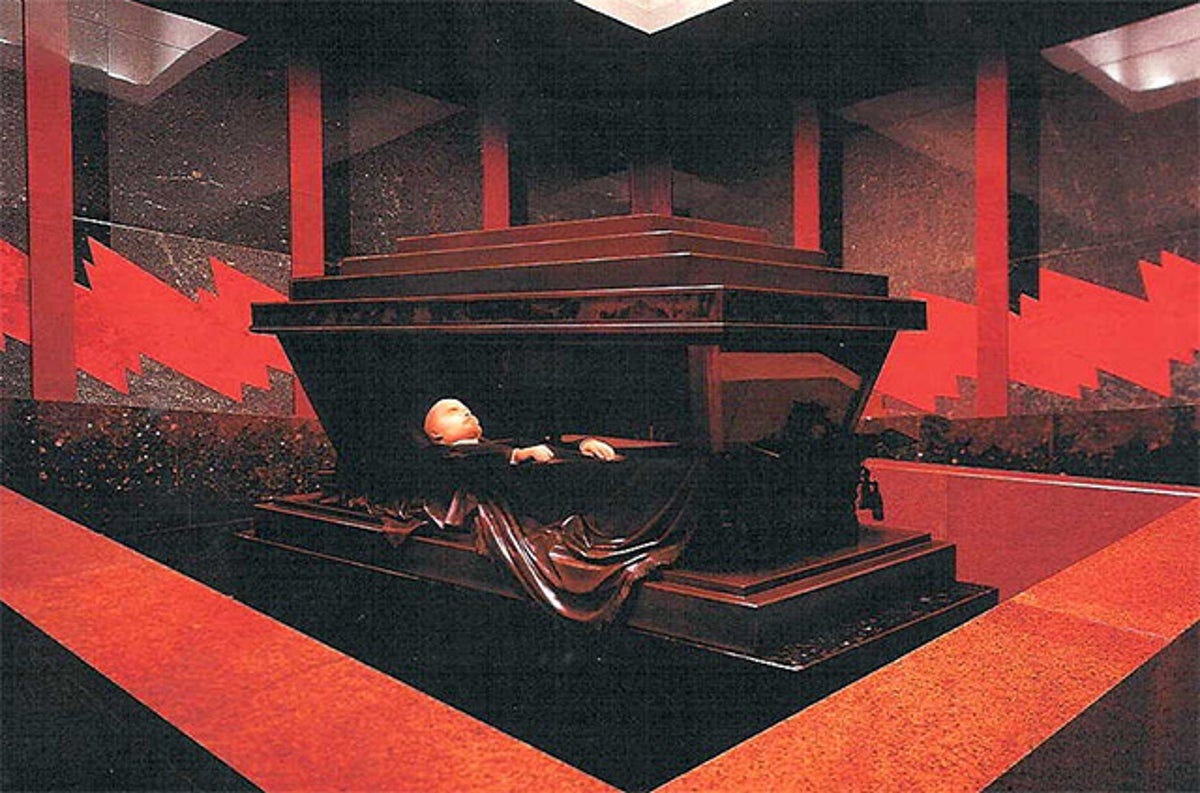

Following Boris Groys, one would be wrong to assume that Stalinist culture was simply folk belief or religion wrapped in a new aesthetic, a notion that collapses essential differences between a Russian or ancient past and the Soviet reality, erasing the historical specificity of Stalinist aesthetics and culture.64 Groys highlights how those who dismiss Lenin’s mummification as capitulation to reactionary religious impulses fail to recognize the novel historical function of the Lenin Mausoleum, which in reality only bore a superficial resemblance to ancient tombs. Unlike the sealed and sacred tombs of ancient rulers, designed to separate the dead from the living, Lenin’s body was placed on public display, and became the most frequented museum in the Soviet Union.65 For ancient mummies, the individual was often imagined as ascending to some kind of cosmic, higher plane, as their embalmed corpses shrivelled up over centuries in dark isolation. Conversely, the Mausoleum was for the masses. It was inseparable from the Soviet state’s legitimizing self-conception as a worker’s state that actively engaged its citizenry through intensive mobilizational policies. In this way, Lenin’s body as a tool of mass mobilization was a distinctly Soviet relic specific to a novel Soviet culture.

Moreover, ancient tombs were designed not merely to house the dead, but to guide the soul's passage into the afterlife. They served as portals between the mortal and divine realms, equipped with adornments, symbols, and offerings to aid spiritual transcendence. By contrast, Lenin’s appearance was meticulously reconstructed to match his living visage—there was no spiritual journey to be had. Lenin was decidedly dead. Despite the preoccupation of some Bolshevik thinkers with immortality and resurrection, the leadership had no interest in keeping Lenin’s body for some eventual Frankenstein-style experiment of bodily resurrection. Lenin’s brain and major organs were removed shortly after death, and his preservation was primarily concerned with maintaining him as an immortalized organic sculpture, an entirely different kind of science fiction experiment. Yurchak writes:

For example, from the beginning preserving a dynamic form of this body—its outward look, weight, flexibility, suppleness, water balance, et cetera—took precedence over the preservation of its actual biomatter … Lenin’s body has increasingly become not a preserved corpse but a constructed sculpture, or at least a combination of the two. Indeed, one of the leading scientists in the lab, and one of my key informants, often describes Lenin’s body as a live sculpture66

Lenin’s preservation was diametrically opposed to the notion of resurrection and stood as undeniable proof of the permanence of his death. If we can speak of Lenin being resurrected, it can only be through “Leninism,” the secular ascension of the leader, and his dissolution into an all-knowing, perfected political form:

Both Zinoviev and Stalin addressed themselves to Lenin as creator and moving force of the Communist Party. “To speak of Lenin is to speak of our party,” said Zinoviev. “To write a biography of Lenin is to write the history of our party.”67

Lenin’s corpse served as the physical anchor for the disembodied voice of Lenin, projected by the Party as a symbol of its pedagogical authority. The Stalinist state was an attempt to cultivate a utopian society, and the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism was the master text—the orthodoxy that served as both the blueprint for social transformation and the basis of Soviet subjectivities, which, through the hand of the Party, were moulded and shaped towards a future, idealized communist subject. Thus, the Soviet citizen “was supposed to be in constant movement, to constantly overcome himself, bring himself further, raise himself higher—both ideally and materially.”68 Under the teachings of Lenin, as explicated by his greatest student, Stalin, man was a self-transforming agent, bringing himself in accordance with the inexorable march of history as led by the Leninist party. In the words of Groys, Lenin had shed his “mortal husk” to become the “the personification of the building of socialism, ‘inspiring the Soviet people to heroic deeds.’”69

The Soviets had transformed Lenin into a permanent fixture of their civic and spatial landscape, intertwining his mythologized personhood with the historical inevitability of their societal mission of socialist construction. The Party’s self-conception as an unyielding and unconquerable political form concealed its ambiguities—between the sacred and the scientific, the historical and the mythological, utility and ideology. These were contradictions of a novel societal experiment always in motion; that is, until the wheels of history slowed and then, suddenly, ground to a halt. Today, Lenin’s Mausoleum is no more than peculiar historical oddity, a remnant of a lost civilization that no longer makes sense outside of its broader Soviet pantheon of labour heroes and revolutionary knights, gods that have long fallen—vanquished by the forces of history they once claimed mastery over. However distasteful, Lenin’s preserved body used to be a focal point of collective memory and ritual that bound a nation, revealing how the Soviet state recognized the utility, if not the necessity, of myth in forging a durable sense of unity and legitimacy. Today, Lenin’s tomb is a relic without a religion, a national symbol without a nation, the ghost of an unrealized future irrevocably stuck in the past.

Read Next:

The Mythology of Lenin's "Testament"

Lenin’s infamous “testament” is an important document to both historians and socialists alike, providing insight into Lenin’s understanding of the Soviet political landscape in his waning years at a time of crucial political importance. It’s also seen as the definitive Leninist rebuke of Stalin. Various historians, including Lars Lih and Moshe Lewin, have written about its enduring political significance, but few have done a textual historical analysis of the document itself and the circumstances of its production. The purpose of this piece is to illuminate the historical context around the creation of the text and delve into the question of its authenticity.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 177, 194.

Ibid., 188.

Ibid., 31, 181.

Alexei Yurchak, "Bodies of Lenin: The Hidden Science of Communist Sovereignty," Representations 129, no. 1 (Winter 2015): 121.

Ibid., 122.

Arch Getty, Practicing Stalinism: Bolsheviks, Boyars, and the Persistence of Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 77.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Alexei Yurchak, "Bodies of Lenin: The Hidden Science of Communist Sovereignty," Representations 129, no. 1 (Winter 2015): 121.

Norbert Nighoghossian, Tae-Hee Cho, and Laura Mechtouff, “Lenin’s Stroke,” Case Reports in Neurology 13, no. 2 (2021): 384–387, https://doi.org/10.1159/000515657

Ibid.

Alexei Yurchak, "The Canon and the Mushroom: Lenin, Sacredness, and Soviet Collapse," HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7, no. 2 (2017): 165–198, https://doi.org/10.14318/hau7.2.021.

Ibid.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 135.

Lars T. Lih, "A Hundred Years Is Enough," Weekly Worker, Issue 1507 (2024), https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1507/a-hundred-years-is-enough/.

Ibid.

Joseph Stalin, Foundations of Leninism (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2020), 102.

Lars T. Lih, "A Hundred Years Is Enough," Weekly Worker, Issue 1507 (2024), https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1507/a-hundred-years-is-enough/.

David Brandenberger and Mikhail V. Zelenov, eds., Stalin’s Master Narrative: A Critical Edition of the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

Ibid., 44.

Kenneth Jowitt, New World Disorder: The Leninist Extinction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 120-130

Ibid., 125.

Ibid., 136.

Ibid.

Adeeb Khalid, “Backwardness and the Quest for Civilization: Early Soviet Central Asia in Comparative Perspective,” Slavic Review 65, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 231–51; David Priestland, Stalinism and the Politics of Mobilization: Ideas, Power, and Terror in Inter‑war Russia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Lars T. Lih, What Was Bolshevism? (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2024), 13.

Victoria E. Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 7.

Arch Getty, Practicing Stalinism: Bolsheviks, Boyars, and the Persistence of Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 76.

Ibid., 77.

Ibid., 76.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 218.

Ibid., 219

Ibid., 84.

Ibid., 174.

Ibid.

Ibid., 292.

Alexei Yurchak, “Alexei Yurchak Explains the Importance of Lenin’s Body: Between Form and Bio-Matter,” Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia (blog), March 8, 2016, https://jordanrussiacenter.org/blog/alexei-yurchak-explains-the-importance-of-lenins-body-between-form-and-bio-matter.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 181.

Alexei Yurchak, "Bodies of Lenin: The Hidden Science of Communist Sovereignty," Representations 129, no. 1 (Winter 2015): 126.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 182.

Alexei Yurchak, "Bodies of Lenin: The Hidden Science of Communist Sovereignty," Representations 129, no. 1 (Winter 2015).

Ibid.

Ibid., 148.

Ibid., 157.

Ibid.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997),187.

Anya Bernstein and Alexei Yurchak, “Sacred Necropolitics: A Dialogue on Alexei Yurchak’s Essay, ‘The Canon and the Mushroom: Lenin, Sacredness, and Soviet Collapse,’ ” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7, no. 2 (2017): 199–216, https://doi.org/10.14318/hau7.2.022.

David G. Rowley, Millenarian Bolshevism, 1900–1920: Empiriomonism, God-Building, Proletarian Culture (London: Routledge, 1987).

Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, ed., The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture (Ithaca, NY – London: Cornell University Press, 1997), 243.

Ibid., 243-244.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 174.

Ibid., 164.

Ibid, 19.

David G. Rowley, Millenarian Bolshevism, 1900–1920: Empiriomonism, God-Building, Proletarian Culture (London: Routledge, 1987), 29.

Ibid.

Anton Vidokle and Irmgard Emmelhainz, “God-Building as a Work of Art: Cosmist Aesthetics,” e-flux Journal 110 (June 2020), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/110/335963/god-building-as-a-work-of-art-cosmist-aesthetics/.

Anastasia Gacheva, Arseny Zhilyaev, and Anton Vidokle, “Editorial: Russian Cosmism,” e-flux Journal 88 (February 2018), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/88/176021/editorial-russian-cosmism/.

David G. Rowley, Millenarian Bolshevism, 1900–1920: Empiriomonism, God-Building, Proletarian Culture (London: Routledge, 1987), 63.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 181, 201.

Ibid., 181.

Ibid.

Ibid., 22.

Ibid., 23.

Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant‑Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 66-69

Ibid.

Alexei Yurchak, “Alexei Yurchak Explains the Importance of Lenin’s Body: Between Form and Bio-Matter,” Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia (blog), March 8, 2016, https://jordanrussiacenter.org/blog/alexei-yurchak-explains-the-importance-of-lenins-body-between-form-and-bio-matter.

Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 97.

Boris Groys, “The Art of Totality,” in The Landscape of Stalinism: The Art and Ideology of Soviet Space, ed. Evgeny A. Dobrenko and Eric Naiman (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 120.

Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant‑Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 67.