Introduction

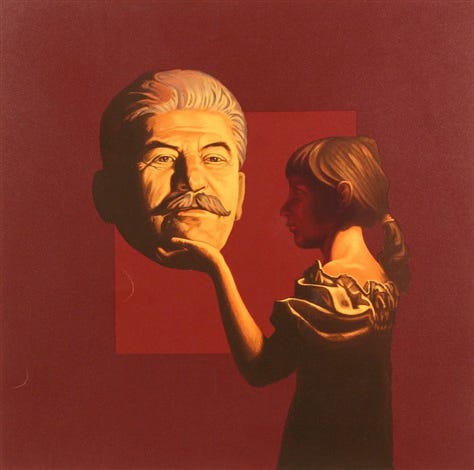

What is dubbed "The Great Terror" is one of the most puzzling events of the century; a lurid, hyper-violent nightmare that entirely decimated Soviet society for reasons which have continued to perplex historians. Conventional narratives about the terror describe it as a top-down series of purges directed by an increasingly paranoid Stalin to…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Stalin Era to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.